KVITVÆRSLEKT 2

Ref.: Konrad Hansen: "A glance at my life" (1971).

KLG 2012

Jens Hansen f. ca 1762, Sandvær, Lurøy, d. 18 SEP 1843, g. Ane Margretha

Jønsdtr., enke etter Christopher Jensen på Nergården, f. ca. 1764

Barn:

Maren Jensen f. 29 SEP 1812

Kristine f. ca 1798

Christopher f. ca 1801, d. ca. 1867

Nils Johan f. 1807, d. før 1868.

Andre generasjon

Maren Jensen f. 29 SEP 1812, Kvitvær, g. 10 OKT 1830, Niels Peder Olsen f.

1792, Sandager, Løkta,

Dønnes, d. 26 OKT 1878, Kvitvær. Maren døde 31 MAR 1886, Kvitvær. I 1865 var

Nils føderådsmann på Nergården (br. 21a), og bodde i en kårstue med Maren.

Mathias hadde bruket og var g.m. Karen, ikke barn. Jensine tjenestepike.

Barn:

Ane Margretha f. 14 APR 1832, død som liten, 20

AUG 1836

Pernille Marie f. 1833, d. 19 JUL 1855, 22 år

gammel.

Mathias Olaus Nielsen, f. 10 SEP 1837, g. 27 DES

1863, Karen Anna Pedersen, f. 1829, Suternes, Lurøy.

Mathias, d. 7 JUN 1913,

drev Nergården til 1894 da Lauritz Larsen overtok.

1. Jensine Marie Nielsen f. 19 MAI 1846, Kvitvær (Nergården).

Tredje generasjon

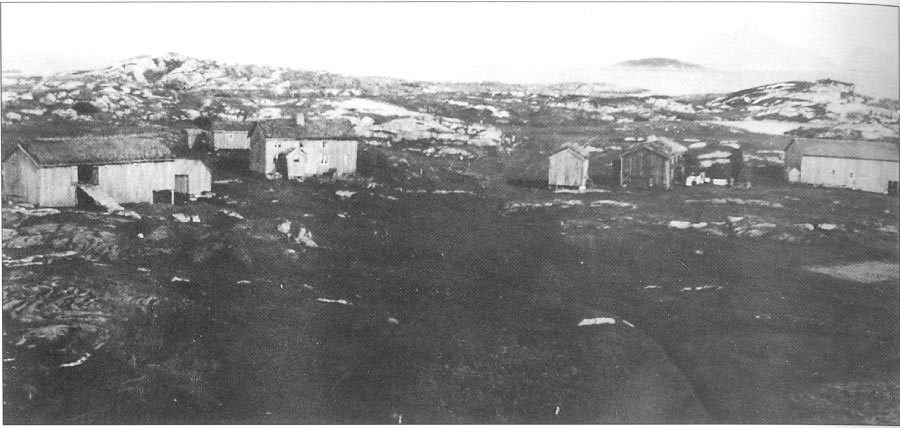

Gårdene på Kvitvær mot nord. Øvergården til v. og Nergården til h.

(Konrad Hansen 1947)

1. Hans Christian Jørgensen f. 12 SEP 1844, Nord-Solvær, Småbruker,

fisker, g. 25 AUG 1870, Jensine

Marie Nielsen, f. 19 MAI 1846, Kvitvær, d. 23 MAR 1908, Kvitvær. Hans d. 17 FEB

1906, Reitgjerdet

hospital i Trondheim, overtok Øvergården, Kvitvær i 1882.

Barn:

2. i Johan Kristian f. 21 AUG 1871.

ii Kristine Marie Hansen f. 28 MAR

1873 Nord-Solvær, sydame, d. 25 MAR 1954, USA.

Var syerske mange år i

Bodø og i Lurøy. Ble mormoner og dro til USA i 1949.

iii Hilda Johanna Hansen f. 26 JUL 1875

Nord-Solvær, d. MAR 1976, USA. Ble mormoner og

emigrerte til Utah i 1910.

G. 7 JAN 1914, Bengt Johnson. Fikk datteren Hulda Marie som giftet

seg med James B. Smith. Hilda og

datteren kom på besøk i Kvitvær og Selvær.

iv Nilsine Parelie Hansen f. 30 SEP

1878, Nord-Solvær, d. 23 OKT 1920, Nord-Dakota, USA.

Arbeidet på restaurant i

Trondheim, ble mormoner. Emigrerte til USA i 1908. G. APR 1915,

Kornelius

Pedersen som hadde gård i

Nord-Dakota.

v Anna Eline Hansen f. 21 AUG

1880, Nord-Solvær, d. 4 SEP 1924, USA. Ble mormoner

og emigrerte til Utah i 1910. G. 6

MAR 1915 Francis F. Crompton.

3 vi Konrad Johan Zahl Hansen f. 31

MAI 1883, Kvitvær, skredder, slektsgransker, d. 10 DES 1979,

San Diego. Dro 18 år

gml. til Trondheim i bakerlære (1901) og like etterpå til Bodø i

skredderlære. Ble mormoner der i 1905 og reiste til Utah i 1906. 15 barn.

Skrevet om sitt liv i: "A glance at my life" (1971).

Fjerde generasjon

2. Johan Kristian Hansen f. 21 AUG 1871, Nord-Solvær, småbruker,

fisker, g. 13 JUL 1897, Lovise

Johanne Dortea Lauritsen f. 26 APR 1874, Lovund,

(datter av Lauritz Larsen og Randine Jonsen)

d. 7 NOV 1960. Johan d. 2 OKT 1943. Han overtok

Øvergården etter faren i 1901 og drev den

til sin død. Sønnen Robert omkom under seiling i 1914. Han var bare 16 år.

En fostersønn,

Ragnvald Johannessen, bosatte seg på Onøy.

Barn:

i Robert Marcelius Pleim f. 7

APR 1898, d. 19 MAI 1914.

ii Dagny Johanna Lind Johansen f. 25

APR 1903, Kvitvær, d. 2 APR 1988, Gift med Einar Holthe

f. 7 OKT 1899, Husby, vegvokter.

Bosted Husby, Tomma.

iii Hans Arthur Johan Johansen f. 5 JUN

1908, Kvitvær, d. 5 DES 1989, Husby, Tomma.

Gift med Ruth Kristiansen

f. 1 JUN 1915, Husby, Tomma.

3.

Konrad Johan Zahl Hansen

f. 31 MAI 1883, Kvitvær, Lurøy Kom., døpt 16 SEP 1883,

Lurøy krk., yrke: skredder, slektsgransker, g. 1 SEP 1909,

Salt Lake City, Rose Elvira Christensen

, f. 13 APR 1887, Murray, Salt Lake, UT, (datter av Mads

Miller Christensen

og Anne Marie Mathiasen Lundgreen

) d. 20 NOV 1969, Salt Lake City.

Konrad døde 10 DES 1979, San Diego, USA, gravlagt: 14 DES 1979, Salt

Lake City Cemetery. Dro til Bodø

i skredderlære 1901.

Ble mormoner der og reiste til Utah i 1906. Fikk 15

barn. Skrevet om sitt liv i "A glance at my life".

Barn:

i

Joseph Leroy Hansen

f. 16 JUN 1910, Salt Lake City, døpt 07 JUL 1910,

gravlagt: 18 JAN 1979

ii

Conrad Deone Hansen

f. 14 OKT 1911, Salt Lake City, døpt 07 MAR 1920, d. 19

MAR 1981.

iii Lillie

Marie Hansen

f. 30 MAR 1913, Mc Gill, White Pine, NV, døpt 1 MAI 1921,

g. 05 APR 1932,

Salt Lake City,

Kenneth Francis Fox

. Lillie døde

27 FEB 1975, Billings, Yellowstone, MT, gravlagt:

03 MAI 1975, Hardin, Big

Horn, MT.

iv

James Edgar Hansen

f. 18 DES 1914, Provo, Utah, UT, døpt 01 APR 1923, d. 25

APR 1981

v

Anna Jean Hansen

f. 13 MAI 1916, Richfield, Sevier, UT, døpt

09 SEP 1924, d. 13 AUG 1924.

vi David

Anthony Hansen

f. 16 JAN 1918, Richfield, Sevier, UT, døpt 06 FEB 1926,

d. 17 JUN 1970.

vii Louise

Aleen Hansen

.

viii Ruth

Ellen Hansen

.

ix Gordon

Paul Hansen

f. 07 MAR 1923, Richfield, Sevier, UT, d. 30 JUN 1930.

x Allan

John Hansen

.

xi Rose

Maurine Hansen

.

xii Enid

Mae Hansen

g. Warren Joseph Wilson

.

xiii Dorothy

Veone Hansen

.

xiv Chan Fredric

Hansen

g. Shirley Jensen

.

xv Eline

Dee Hansen

.

Mormoneren fra Kvitvær

Hans Kristian Jørgensen fikk 2 sønner og 4 døtre. Yngste sønn Konrad

Johan Zahl Hansen ble født i 1883. Han dro først til Trondheim 1901 i bakerlære.

Det var et hardt liv og Konrad kom seg derfor til Bodø der en eldre søster

(Kristine) var syerske. I Bodø kom han i skredderlære og ble mormoner. Han

fikk lån fra dem og emigrerte til USA i 1906. Han skrev boken "A glance at my life"

(1971) der han forteller litt om livet på Kvitvær. Hans morbror Mathias

Nielsen forpaktet den andre delen av Kvitvær (Nergården). Den ble overtatt av

Laurits Larsen i 1895 som fikk 7 barn og en av dem, Richard Larsen (f. 1882),

ble en god venn av Konrad. Konrads bror Johan Kristian Hansen ble gift med en søster

av Richard (Louise). De bygde hus på Kvitvær og døde der. I 1946-48 var

Konrad på misjonsoppdrag i Norge etter å ha vært borte i 40 år. Han besøkte

Kvitvær juni 1947 og tok et bilde av gårdene som enda sto der. Alle Konrads 4

søstere emigrerte til USA.

Konrad besøkte Richard Larsen på Selvær og

datteren Olga husket godt dette. De hadde mye å snakke om og Konrad var meget

interessert i folk og slekter da han var slektsforsker hos mormonene. Av og til

slo han over i engelsk. Da slo Richard neven i bordet: "No snakka du

norsk!". Slikt ville ikke Richard vite av enda han snakket godt engelsk

selv. Olga var flere ganger på Kvitvær som liten omkring 1920 sammen med faren

for å besøke sin farfar som bodde på kår i ei gammel stue på Nergården.

Avskrift av

av boken til Conrad Johan Zahl Hansen:

A Glance at My Life, Provo, Utah, 1971

(Kun de første sider som omhandler Kvitvær)

Place of Birth

My

life began in the arctic region of northern Norway, or to be accurate, where

the Arctic Circle intersects the west coast of Norway. This northern region is

well-known by tourists and travelers as the area of the midnight sun. This

fringy coast decorated with hundreds of islands makes an interesting design for

painters and poets who are seeking inspiration and the perfect setting for a

personal artistic work. High mountains stand firmly above the sea, watching the

lower islands scattered around them all along the coast. The islands come

generally in groups, and each group has a name according to the appearance and

size. Each strip of ocean has a name, if for no other purpose but to aid the

government in making maps for the transportation along the coast. The names

have changed a trifle during the past centuries, but merely to conform with the

style of the later inhabitants. One group has bleach-white rocky reefs, and

perhaps originated the name Kvitver (White Group). At this place I was born,

and lived with my parents and their people during childhood and youth. This

group is small and not very prominent, but is located close to the main route

of traveling going north and south.

The

main island of Kvitver is approximately three (3/4) miles long, and nearly as

wide, with several smaller islands closely connected to the main island on

every side. These islands are hilly, and the summit of the highest hills gives

an extensive view over the ocean in all directions. The indentation of the

shores into nooks and corners makes the island well-adapted for landing small

boats and for erecting boathouses. There is also a convenient and safe harbor,

surveyed by the government for entering and anchoring large vessels.

During

the year it rains considerably, so fresh water is not a problem. The main

island has therefore many glittering ponds. But on this windy island, there is

not any forest. No, not a single tree has ever grown enough to be called

anything else but a bush. The green grass and wild flowers decorate the hills

and meadows sufficiently during the summer season to satisfy the people living

there, and we never longed for shade trees or forest. Neither did we have such

sensations as the wind rustling in the tree tops. Our neighbor did plant one tree,

and in forty years, when I returned from foreign lands, it was as tall as a

one-story house.

Yes,

this is the land of the midnight sun. Through the lustrous evenings and

mornings the sun moves slowly through drifting clouds and produces grotesque

sceneries. The glorious summers therefore attracted people from many places for

a brief summer vacation.

But

northern Norway also has long and dark winters. The winter is often twice as

long as the summer. However, the spring weather changes quickly from winter to

spring. Violent storms and short days are not inviting features for tourists

and travelers. Were it not for the moderation of the ocean it would be bitterly

cold. The current bearing north keeps the icebergs away from the coast, and

this moderates the climate considerably.

In

many ways it has been a pleasure to have lived in such a beautiful land, and to

have personally known such noble people as my early associates, and my

honorable ancestors, who lived for centuries under these extremely changing climatic

conditions on these scattered islands along the coast.

My

Parents

In

writing about my parents I shall begin with my father, who was two years older

than my mother, not merely in years, but also in the art of sailing his toy

boat in a shallow washtub, till his determined mother called: "Now Hans!

What are you up to?" This advancement in time lasted all their life, till

my mother decided to get even with him, as she lived two years longer. They

both died at the age of 62, without a divorce, and without any praise at their

funeral services.

My

father, Hans Kristian Jorgensen, was born on the 12th day of September, 1844,

at the island of Nord-Solver (North-Sun-Group), a neighbor island west of

Kvitver. This island has three farms, a general store, and a post office, but

no doctor or trained nurse in the district. My father was the fifth child of a

large family of 12 children. His parents owned a farm, and were therefore in

moderate financial circumstances.

Then

something grievous happened. My father and my grandfather rowed two boats

around their island. A violent windstorm arose, and my father drifted to a

small island and leaped ashore. The boat was damaged, but he was rescued. My

grandfather rowed the largest boat, and was unable to handle it properly, so he

drifted towards the open sea and never returned. He was then 60 and my father

was 21. The church record of Luroy Parish states that my grandfather, Jorgen

Johan Mortensen, drowned on the 17th of May, 1865, and that his burial took

place August 13th the same year, indicating that the corpse was found in the

summer of 1865. He had, therefore, a decent burial, which was highly

appreciated. My grandmother, Ane Elisabeth Christoffersen, was then 47 years

old, and had ten living children. The youngest was only two years old, but the

three oldest children were married, and my father, being the oldest of the

seven children at home, helped his mother with farming and fishing for several

years.

Sometime

after my grandfather's death, my grandmother married Kasper Hansen, from the

city of Bodø. He was attracted to this island by a herbalist. He was ten years

younger than grandmother, and the inducement was that he would be a great help

to her, for she owned a farm and home. But evidently he was not in good health,

as he died many years before my grandmother.

My

father was not badly needed at home then, so he began to plan for his own

future.

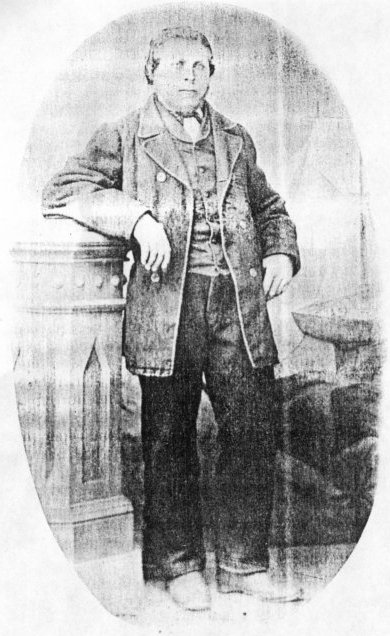

My

father was a practical man, not very large, as I remember him about five feet

and eight inches tall, and approximately 165 pounds. He wore a short beard, as

this was in vogue at that time, and he was of fair complexion. He had trouble

with his suspenders to make them stay on his sloping shoulders. He was

talkative and pleasant in his crowd. His scholastic education was limited, yet

he could write legible and interesting letters, and read fluently. In his

social functions he was modest, and did not drink intoxicating liquor, neither

did he use tobacco in any form, which was unique at his time.

At

the age of 26 he married my mother from the island of Kvitver. They were not

related, but attended the same school and the same church. I know very little

about their courtship. They maintained enduring love without much display.

Affection was not on exhibition among the people in the district, neither was

it considered graceful manners to embrace and hug and kiss each other in their

public gatherings. They were modest and very helpful to one another, so their

custom could well be considered a love affair, with high esteem for one

another's ability and rank. My father was at times hasty, but he generally

displayed a sense of humor. He was 39 when I was born, and I therefore missed

his early marriage interest.

To

write about my mother is to call my fond concepts into motion, and I trust that

it is not in vain. Her tender feelings and fine attitude may be exaggerated

against a common social surrounding, but even at that she possessed a glorious

refinement and noble character, which shall always be remembered by those who

knew her well. My mother, Jensine Marie Nielsen, was born the 19th of May,

1846, at the island of Kvitver. Her father, Niels Peder Olsen, was a farmer and

fisherman and came from Sandager, on the island of Lokta, about 40 miles south

of Kvitver. Her mother, Maren Jensen, as well as several of her maternal

ancestors were born at Kvitver. My mother was the youngest of four children,

with two sisters and one brother. The oldest sister died as a child, the next

sister died at the age of 22, and her brother was our neighbor for many years.

How it happened that her father traveled a long distance and married her mother

is not known, he 39 and she 18, but their homes were on the main sailing route,

and it is possible that he traveled on a fishing trip, stopped at her place,

and fell in love. My grandfather, Niels Peder Olsen, died in the year 1878,

five years before f was horn, and my grandmother, Maren Jensen, died in the

year 1886, three years after my birth. I have only one recollection of seeing

my grandmother. I visited her while she was sick in bed, and she reached for a

cookie and gave it to me.

Mother

disliked the ocean, yet she dared to travel over the sea in a small boat to the

church and to her friends. She never traveled far from home, and she never

boarded a steamer. Her education was the grade school, plus the domestic

training at home which was very extensive. The schoolteacher sold text books,

and the minister distributed Bibles, and in later years a magazine came

periodically, which apparently covered her literary attainment. Mother was

artistically inclined, and often displayed her interest in beautiful sceneries.

Through childhood and youth she learned to like this island. Artistic talents

are often burdensome in a frontier society, but people can adapt themselves to

various conditions and be moderately happy. My mother was very attractive in

her youth. Her black hair, blue eyes, and slender figure perhaps drew more than

one admirer; nevertheless, she married an ordinary farmer and fisherman from a

neighbor island when she was 24. I did not remember her before she was about

40, so I missed some of her youthful glamour. But her deep-rooted concern and

profound love displayed at middle age were more than skin-deep. I loved my

mother very much.

After

my parents married they settled at Nord-Solver, Father's birthplace, where they

built a home and lived for several years. My brother, Johan Kristian Hansen,

and my four sisters, Kristine Marie Hansen, Hilda Johanna Hansen, Nilsine

Parelie Hansen, and Anna Eline Hansen were born there. My father depended on

fishing, but this was not sufficient to meet the demand of an increasing

family. After 12 years of marriage my father sold his home to his younger

brother, Johan Edward Jorgensen, and leased half of the island of Kvitver from

a wealthy landowner. It is likely that my mother favored this move because her

brother leased the other half of the island, and it was her home island. The

buildings on the farm were all dilapidated, and to rebuild and repair them took

many years. Both farming and fishing were in many ways an advantage to the

Family. The farm was large enough for planting barley and potatoes. They

generally kept four milk cows, a dozen sheep, and one half a horse; that is,

they had a horse together with the neighbor. The farming gave very little in

cash, but there was a prestige to being a farmer and a fisherman that was

always used in connection with any records of the church or in census records.

My father paid 200 kroner in cash (about seven kroner to a dollar), and 20

kroner each year for the lease of half of the island of Kvitver. There was no

distinct marker between the farms. My uncle knew the dividing line, and he was

not greedy.

My

parents were striving hard to support their family and to meet their financial

obligations honorably. This we knew perfectly well, so we had high regard for

one another in the family. But it was hard work always for every person,

without dispute between each other.

|

|

|

|

Birth

and Infancy

One

year after my parents moved to Kvitver, I was born. That I remained the last

child in the family cannot be blamed to an indifferent attitude, because my

mother had six children, and was then 37 years old. She told me that I was born

on the last day of May, l883, and she

ought to know. There was no medical help on our island, so a midwife was

therefore fetched from another larger island. Had it been in the winter, help

would be uncertain, but in May it was different. A small boat fluttered over

the waves by rowing or sailing, and returned in less time than expected. The

day is long enough in May to eat supper, read the evening prayer and retire in

bright daylight. The praying was often but a sigh, or a sincere wish, but why

bother providence with so many small items which they could do themselves.

However, now they were grateful that all went well. I was at least a normal

child, and a change from four girls in succession. It is wonderful how life is

preserved from birth, even with such limited medical assistance. To tie and to

cut the umbilical cord and then cover the child's navel with a bandage was the

important part of the medical help applied. But all went well with mother and

child, at least in this case.

My

mother nursed her children at the breast, and if this was not sufficient a

nipple made of cloth containing sweet, mushy ingredients was an ordinary

substitute or aid in the process of nutrition. Whether this method should be

considered strictly sanitary is a medical problem and ignored or unknown by my

parents.

At

the age of three months, I traveled seven miles in an open boat to be

christened in the Lutheran Church. According to their belief this was very

important. If a child was sickly, and could not be taken to church, baptism

could be done at home then recorded later in the church record. My godparents

accepted with pride the full sponsorship, which was not just a momentary

display at the aisles of the parish church but an obligation to care for the

child if needed, and to teach it the Christian religion. My full name, Konrad

Johan Zahl Hansen, was selected by my mother according to her best decision.

In

spite of all precaution, I was at first considered a puny child. Mother nursed

me carefully, yet I maintained that slender, long-legged appearance which is

common among puny children. We feared the long winters, as the cold wind

penetrated our home. The coffee in the kettle froze solid overnight, which was

our thermometer. My mother manufactured our clothes of wool and plenty heavy.

The beds were deep enough for a straw mattress, a blanket, and on top a

sheepskin quilt with the wool down. All clothes for the children were homemade

by my mother, so during the dark winter season the work indoors consisted of

carding, spinning, weaving, and knitting. My father repaired fishing nets and made

new ones. He also made wooden shoes for everyone in the family, so during the

winter our home was a workshop. We had plenty of space, as the living room was

large enough for a loom, a spinning wheel, and for stretching out the fishing

nets. My parents never worked on Sunday, so all work had to be done on

weekdays, except the chores on the farm which were daily requirements. Sunday

was the day of rest, and was often celebrated by delicious food and religious

worship.

Childhood

As

a child I was safe around the house and on the farm, and there was plenty of

space for playground, so I did not cause my parents much anxiety as I roamed

around. Our home was built in the center of the island, and from the home to

the boathouse was a rocky trail, uninviting to a small child. But as I grew

older the long beaches with pebbles and sea shells attracted me. Nature

provided for our entertainments. In sailing my toy boats I preferred the ponds

rather than the ocean, as I had the sad experience of losing a toy boat on the

ocean. When the winter froze the ponds, we practiced ice skating. We made our

skates of discarded scythes which were fastened to a board and strapped to our

shoes. Often I would toss myself prostrate on the ice and gaze at the ice

crystals in the translucent floor. It was a healthy sport, and we enjoyed it.

Over the summer months we picked many kinds of berries, and we also hunted

eggs, as there were many varieties of sea birds. The eider ducks were most

valuable, because they produced both down and eggs. We always left two nest

eggs, so the birds would be sure to hatch at least one. Otherwise, they might

not return the next year. The midsummer festival was celebrated with a huge

bonfire at the top of the highest hill. In the past the windward side of the

summer stable was selected and empty tar barrels were burned. The smoke would

then disinfect the stable from any evil omen, but we chose the highest hill for

display to compete with other islands which took part in the celebration. The

summer nights in the arctic were enchanting. The east breezes fanned a fresh

odor from the pine forest of the mainland which we indulged in at that time of

the year, as the smaller islands are void of any forest.

One

of my first responsibilities was to herd cows, as there was not any fence

around the fields. There was plenty of pastureland on the hillsides and over

the meadows. My youngest sister was my companion. In the noon hour we drove the

cows over a sand bar to a small island while we went home to lunch. At high tide

the cows had to swim or wade across the bar. We had a horse to pasture, but it

chased the cows, so when the planting was done, we swam the horse to another

island. This was our rodeo. The horse was led by a small boat, but when the

boat returned, the horse swam back to the main island. After a couple of trips,

though, the horse settled down. There was plenty of feed and water in the new

pasture. We also pastured sheep on several islands, but they became shy and

were hard to catch later.

The

summer was short, and we were busy with many things. Fuel for the long winter

was always important. We used peat as a substitute for coal. On certain

hillsides the soil was cut in cubes, then sliced and dried in the sun. We also

purchased wood from sawmills, so we traveled south for 50 miles in a large boat

and loaded it to capacity. This was sufficient for a year supply. These trips

in the summer were always interesting, as they took us through long fjords

where the forest covered the mountains everywhere. The logs were drifting along

the shores, which was not in harmony with our economy. When we came home the

boat was unloaded, and the wood was piled in the boathouse. Everything had to

be under shelter: peat, wood, and fish, as well as all crops from the farm were

inside some substantial shelter to protect them during the winter season.

There

were often things of interest on the islands. Once the Laplanders invaded our

island with several hundred reindeer, and with many trained dogs. They swam the

reindeer across the fjord to our island to pasture them for two days, as the

feed was scarce in the mountains. Perhaps they overestimated our pasture. In

parting they swam the reindeer back. The leader was tied to a boat, and the

rest followed in close succession till they arrived safely at the mainland. The

Laplanders are not poor, but they are gifted beggars. My youngest sister and I

retreated to a corner, as we were frightened by the appearance of the

Laplanders and their black dogs.

Winter

sceneries were often fantastic. Once my sister and I roamed over the island,

when suddenly a flickering light spread above the horizon. We were amazed, as

the dark arctic nights are never penetrated by any artificial light. The snow

glittered faintly as the light waves arose to the north and spread towards us.

"Look!"

exclaimed my sister and pressed my hand, "The northern lights!"

We

both gazed at the spectacular waving of the aurora borealis. It flowed like a

tremulous fire with stripes of flaggy sheets in many colors. The light whirled

into fanciful ornaments, then vanished swiftly.

We

had several companions on the island. When my uncle, Mathias Nilsen quit

farming, a new family took over the farm. Laurits and Randine Larsen, from the

island of Lovunden, with seven well-behaved children gave us plenty of good

companions. They were some of our distant relatives, and they were

exceptionally good neighbors.

Uncle

Mathias was over eight years older than my mother but he was able to do

ordinary light work. He was rather of the stern type, In the early morning he

would often feast on cod liver and flat bread, but the other meals had to be

fish and potatoes. He had two boats, one for fishing and the other fur taking

some of us to church. On Sunday morning he walked with long and precise steps to

the boathouse to get the boat ready. He would sometimes wait an hour or more

for everyone to get ready. His boathouses were orderly. When sawing wood he

measured the length with a ruler, then stacked it along the wall.

Uncle

Mathias' wife, Karen Anna Petersen, was a crippled woman, not from childhood,

but from maternity confinements. She was a small woman, and walked on crutches.

She was the much needed encyclopedia and genealogical almanac of the island.

She did not gossip, but could inform one of many things. In my genealogical

research of later years I wished that it were possible to talk to Aunt Karen.

She did not attend church, on account of her crippled condition, but she gave

herself to her neighbors, in particular to us children. If her liberality

afforded but a small cookie to each of us, it was Aunt Karen's gift to the

world without recompense. Neither did she expect any reward, as people were

liberal in our district.

School

Days

At

the age of seven I was sent to school. The teacher, Erland Christensen

Brandser, was my uncle-in-law, as he married my father's sister. He came from

Brandser, Gudbrandsdalen, but was educated at Troms Seminary, at Northern

Norway, and settled as schoolteacher at these islands for the balance of his

life. He knew very little of boatmanship, so when he freighted his equipment

from one island to another the boat often wrecked, and he rescued himself by

swimming. At that time there was no schoolhouse in our precinct, so sessions

were held at farmhouses. The largest home on the designated island was used as

schoolhouse, A long table, resting on crude jacks, was placed in the room, with

one long bench on each side. These tables were slightly warped and knotted, and

had three inches play lengthwise, which created considerable argumentation

during the penmanship period. We took turns pushing the table. The teacher at

the chalkboard held a small mirror above his shoulder to detect the guilty one,

but we watched shyly our chance. The alphabet and the numbers we knew from home,

so we began with reading, arithmetic, penmanship, and behavior. We furnished

our own school supply including all books. Our parents could not always buy all

the books we needed, so we borrowed books from the children at school; however,

they often refused to accommodate us. In spite of those conditions, I managed

to study my lessons each day, so I received good marks in all the subjects.

Only one grade for children from seven to fifteen was in many ways detrimental

to the children, particularly for the younger and the older.

This

was not a boarding school, and we were several miles from home, so we lodged

with a friend or relative who lived on that island, and we furnished our own

provision. We brought with us a large trunk of food, which was sufficient for a

few weeks session, and the family we stayed with furnished us with a meal each

day.

The

school was supervised by the minister of the Lutheran Church, and we studied

the Bible and catechism. We also attended church services frequently at the

Luroy Parish Church. There we met many of our friends. People congregated at

the churchyard, which was also the cemetery, for business propositions, or for

merely leaning on a tombstone while telling fish stories till the toll in the

steeple called them to the interior.

The

cemetery was not a place for gaiety nor for displaying of trophies. Most of the

people attending church services had some relatives buried there, and it must

have reminded them of the sadness of past events. One of the events that I

witnessed was the funeral procession of my uncle's three children. The oldest

son, 22, and the two oldest daughters, one 20 and one 18, sailed a boat and

wrecked, drowning at the same time. To see the three coffins carried along the

road with two men leading the procession and singing a song, and the parents

following after, was the most unforgettable event of my young life. I was then

17, and old enough to notice my uncle and his wife bowed in sorrow, with

tear-stained faces, walking the dusty road to the cemetery. None of the three

children were married, and perhaps have been forgotten long ago, unless the

Salt Lake City Temple records shall testify of our work for them.

My

uncle, Jacob Andreas Jorgensen and his wife, Ane Marie Karoline Pettersen, had

a large family, and during that accident which happened to their children, they

must have grieved very much. They were poor and no help was available, at least

in cash, at that time.

If

anything prevented us from going to church, my father conducted services at

home. The program consisted of singing, praying, and reading of a sermon

written by a minister. These sermons seemed unusually long, but silence was the

only requirement of us children.

At

the age of 15 I graduated from school by attending a six weeks session conducted

by the minister. At the graduation exercises the pupils stood along the aisles

of the church and were questioned by some dignitary in his complete vestment.

The interior of the church was decorated with fresh foliage. The graduates wore

new clothes and received special attention. It was an important day, as I was

then through with school, and the free life of a young man was before me. It is

regrettable that in my reflections afterwards I did not long to go back to

school. Perhaps the method of teaching was not interesting. It may be too that

my association with a crowd was in contrast with conditions at home. My work

was often done in privacy, and my play was sometimes a solitary amusement.

At

the age of 13 I met with an accident. My mother wanted me to chop kindling,

which was everyday work for me. We had some boards from the sawmill which we

used for wood. I wore gloves and the ax was heavy, so I spread my left hand on

the board to keep it in place, and I cut my middle finger nearly off below the nail.

I ran to the house, and Mother put a clean cloth around my hand. My father and

brother and neighbor took me in a rowboat to the doctor. The doctor put me to

sleep by using chloroform, so I felt no pain. The end of the finger was covered

with the skin of the fingertip, and sewed on. The next day I went home with the

arm in a sling, and two weeks later I returned to the doctor. The finger healed

nicely and I had no trouble, but my left hand was weaker, and the middle finger

an inch shorter ever after.

This

was perhaps one of the reasons why I went to the city to learn a trade.

Had

this accident happened at the age of 23 it might have been said that I cut my

finger off to avoid being drafted to war, as I never had any admiration for a

warrior, not even Goliath of Gath, neither was it stylish to be a conscientious

objector in our community. This was my first experience at a community

hospital. Among other advancements, I noticed a nurse make a long-distance call

over the telephone, and she was as much surprised to get an answer as was I.

How words can travel along a wire has always been a mystery, as well as travel

without a wire to objects in motion. The advantage is that we don't have any

trouble with the wire.

Fishing

My

early training was very practical. In the summer I helped my father with

fishing, which was mostly rowing the boat. The ocean was common property, and

the bottom was well-known to my ancestors from father to son, and had names,

like places of interest in a city. We had no need of navigation, as all fishing

was done with land in slight. The compass was the only instrument in our

possession, and it was seldom used. It was there that I received my early

training. We dealt primarily with nature, and the laws of nature are firm. We

did not sleep at work and let the boat drift. In a boat there is only one inch

between life and death, but in our case it was only half an inch, as the small

boats are built of thin lumber. Where we were fishing the depth was several

hundred feet, and the dread of the invisible was often exaggerated, at least

among children. Think of the myriads of creatures, from a speck to a monster,

that could tap or crush our boat in a second. But fear was not our weakness

generally. Perhaps we were too practical, and were burdened with caution.

However, we were by necessity obliged to work, and the sea was an important

resource, so we became attached to it. The winter was the best season for

fishing. From January to April the cods streamed in from the deep sea to the

shallow water to spawn, and the uttermost islands were therefore headquarters

of the cod industry. The famous fisheries at Lofoten attracted men from the

entire coast of Norway. The island of Lofoten is several miles north of the

Arctic Circle, and the winter has very little daylight. Storms rage

continually, and many sacrificed their life in the struggle for existence.

One

winter I went to a station near my home in company with my brother and our

neighbor boys. The fishing was poor, but the experience was valuable. At a

certain hour each morning the sheriff hoisted a flag, and all sailed at the

same time. Each boat could then protect its own fishing lines from being

interfered with. Most of the boats had a crew of five men, but one boat had

only two. The boat was small, but they were cautious as the fishermen had

learned to be. They sailed in rough sea too, but always with the proper

ballast, and the right canvas. On stormy days we lounged in the cabin. On the

wall hung a barometer, and the men clustered about it several times a day, as

it fluctuated considerably in changeable weather. After three months we arrived

home safely, but with a small profit considering the hard work and the risk.

Fishing

was hard work and I disliked it. I preferred to be employed on the land, but to

change occupation was not possible then. My mother once said that I ought to

learn some thing else, but she could not propose anything then. A higher

education was very expensive, as there was not any free high school. The

tuition alone cost 50 kroner a month. School supply, board, room, and clothing

could well amount to more in cash each month than a fisherman could provide for

in a year, so a higher education was primarily for wealthy people.

So

my urge was to go somewhere else or do something different. It took

considerable courage to leave home without money, but we were located close to

the main sailing route and were in touch with people from a wide area. This

bolstered my confidence in strange people. I was taught good principles, but they

could not be bartered for anything valuable or for cash. My earning at home was

so insignificant that it would scarcely supply me with the most essential

things. My earlier amusement around my home did not attract me now, and some of

my companions had left for other places. So I waited a couple of years for

further development. In youth a year seems an extremely long period, and

impatient as I was, time dragged slowly and tediously.

To the City

At the age of 18 I left home. One of my cousins, who lived at the city of Trondheim, informed me of an opening there. It was at least a chance to try a city. My parents gave their permission and enough money for the journey. The city of Trondheim is located in central Norway, south of my home, and had then a population of 50,000. I had never seen a town of over 1,000, so I was amazed. My cousin met me on the pier and took me to a reasonable hotel. The next day I began as an apprentice in a large bakery. Several people were employed there. We worked 12 hours daily and part of Sunday. It was difficult to adjust myself to the new work, and after a short time I felt dissatisfied with my job. The apprentices were subject to ridicule, and occasionally sent on fools' errands. My companion was sent to a bakery to borrow a device which did not exist. The other bakery sent him to a third, and so on till he had called at several bakeries. A friend told him that his boss was fooling him, so he complained to the owner of the bakery, and threatened to quit, which did not improve the condition. The boss generally carried a hatchet in his hand and pointed with it, and if annoyed he would, without hesitation, fling it at the offender. Our sleeping quarters in an attic room accommodated four of us, and was seldom cleaned. To complain as my companion did was useless. I soon learned that apprentices could not expect decent treatment. Alter two months I was so disgusted with everything connected with my job that I decided to quit, as I had not yet signed a contract.

At that time my oldest sister lived at the city of Bodø, and she wrote to me, asking me to come. It did not take a great deal of persuasion to convince me to go. The city of Bodø is located about 80 sea miles north of Trondheim, and the ticket cost more than I expected, but I boarded the steamer anyway. It was three days' journey, and I had no other food but a loaf of bread and a few rolls from the bakery. After two days we passed my home island, and it had a friendly appearance. Before reaching my destination I had to purchase the ticket. I feared that my cash was insufficient, so I thought at first to fool the captain by telling him that I boarded the steamer at a different place; but I was not used to deceive people, so I walked into the captain's office and asked for a ticket. He glanced at the chart and quoted the price. I put all my money on the table and said, "I am short one half krone, but I have some postal stamps to cover the balance."

"I have no use for stamps!" he replied angrily, but he took the money and flung the ticket over to me. He considered me a stowaway or an undesirable person. One hour later the steamer anchored at Bodø harbor. All passengers landed in a ferry, free of charge; otherwise I would have had to swim ashore. With my suitcase I rambled along a street till I noticed the sign of a small hotel. Here I rented a room, and trusted to borrow money from my sister to pay for it.

Sister Kristine was working for a dressmaker, and rented a room together with Petrine Sorensen, a girlfriend. She paid for my room and gave me meals which I appreciated highly. She also introduced me to a friend who was a tailor and operated a tailor shop He offered me work, and also gave me a day to see the town. This was June, the best month of the year, with sunshine day and night.

The city of Bodø is a seaport city, and had then a population of 5,000. The only projections above the uniform roofs were the spire of the largest church and the chimney of the brewery. Main Street was decorated with slab sidewalks and a lamppole on each corner. In one day I had seen the city, but the surrounding country was unexplored.

It was high time to begin work, and I was very anxious to get started. I did not choose tailoring, but I needed a job. I wanted meals and lodging, and I did not know anything about trades. It was early morning when I entered the reception room of Edvard Larsen's tailor shop. After a few questions I followed Mr. Larsen into the workshop. I was not introduced to any of the workers, but simply assigned to a workbench as a helper to an elderly lady. She was very nice to me, and displayed her good-natured disposition in humorous expressions. Every day I had to deliver clothes, and many of our customers lived out of town. These errands made the day shorter, as the work in the shop was very confining at first.

My boss, Edvard Larsen, occupied a nice apartment and dressed well. He was a single man then, and occasionally entertained small parties at his home; but he often attended religious meetings. It was there that my sister met him, as she went to the same meetings. I knew some of his private affairs, as I lived in his apartment. He lived a Christian life. Every morning and evening he knelt by his bed in prayer. His conduct otherwise was also in harmony with his religion, but he was more humorous than most of the Christians. He belonged to the Inner Mission, which was a group of the Lutheran Church. If my recommendation were needed I could only say that of the thousands of people that I have met Edvard Larsen is the finest man I have ever known.

In the tailor shop we began work al seven in the morning, and it lasted till nine at night. Fourteen hours was too long for a beginner, but it was not hard work. After two months I signed a contract to serve a three years' apprenticeship. Besides board and room I received in salary 50 kroner in three years. The tailor shop was a college of ethics and refinement, so I was attracted to it. My companions were cultured, religious people, and I was so pleased with this environment that the value or rank of my trade was not considered seriously.

One of the privileges of an apprentice was to attend a technical night school. It was conducted by the state and free. My boss was opposed to the school, but with some persuasion he finally consented. I enrolled together with 36 students. This school was running two hours each evening, five days a week, for three successive years. The subjects taught were grammar, bookkeeping, mathematics, and drafting. I was one of the best in drafting and received a prize, but some of my ornamental drawings were kept by the school for future display.

One year after I came to the city of Bodø I joined a temperance society. It was merely for social reasons, as several of my acquaintances were members. This society was a local branch of a national organization. At our weekly meetings a program was arranged for, and refreshments served. During the summer we took several excursions. The society hired a steamship over the weekend, and these excursions were very interesting. The president of the society, Lovise Engen, and her brother, Anent Engen, were in the photography business, and were highly respected business people. I appreciated the social functions of these people, and credit this organization for some of the finest influences in my life.

Outside this organization there was very little amusement. A young man started a bicycle business, and every youngster in town rented a bicycle. One of the boys drove his bicycle through the office window of the prosecuting attorney, but he escaped with a few scratches as the attorney was not present. I rented a bicycle till I learned to ride it, and that was all I could afford. As a substitute I went hiking to the mountains, in company with my test friend, Johan Lokaas. We got permission from the tourist society in town to use their cabin on the top of a high mountain. The cabin was built at a vantage point for seeing the midnight sun. This cabin was equipped with tables, benches, and cooking utensils, so it was a nice place to stay. We were of course responsible for any damage done while there.

Each summer I had a vacation for one week. It was lovely to come home to the old familiar place and visit with my parents. I rambled over the hills, around the ponds, and along the beaches. It was all so familiar to me, but merely a glance into my child-hood, altogether too brief, and not my home anymore. I had to rush back to the city and to the tailer shop.

The three years of my apprenticeship passed moderately fast, and in June, 1903, I commenced as a journeyman working for salary. I soon discovered that my income was modest, and had to be handled with care. The older tailors maintained that I was living in a new era of advancement and ease, that in the past all tailors worked from four in the morning till eleven at night and then slept at the workshop. I appreciated the new era, with a much shorter workday, a nice room of my own, and some education. As a journeyman I was more respected than before. People talked politely to me, and ladies recognized me in the street. Not that I craved the companionship of ladies, for I was only 21 and much too young for a steady girl companion. Neither was I connected with any social affair that expected an exceptional personal behavior. In truth my fundamental training from home was not improved on by city environment. Yet a small city is in many ways a good place for training an individual. Here one approaches great persons of different pursuits, and is not forced to maintain a general opinion, or to follow a certain occupation, if it does not interest him.